By Peter Reat Gatkuoth

ABSTRACT

January 3, 2019 (SSNA) — Following the commercial discovery of oil and gas resource in the country, Uganda has instituted a detailed policy, legal and institutional regime to direct the exploration, development and production of oil and gas resource. Research reveals that Uganda has incorporated the concept of punishment and persuasion in the regulatory regime for oil and gas sector, which is based on core principle that a ‘sector regulator should be separated and must be independent from the entities being regulated and that penalties must be set against those who violate regulatory rules and practices.

In addition, the existing framework provide for a network approach to regulation, with the law mandating several government entities to regulate specific aspects related to employees in the oil and gas sector. The author seeks to analyze the synergy between the concept of punishment and persuasion; it’s applicability in Uganda’s regulatory regime, the basic criticism concerning the two concepts, challenges and recommendations thereof. The author notes that despite the incorporation of such concepts in Uganda’s regulatory regime for oil and gas sector; this submission does not guarantee strict compliance of such rules set to regulate the sector.

Introduction

In order to successfully explore, develop and produce oil and gas resource, Uganda like any other countries has enacted and passed several laws in order to realize this goal. However, B.K Twinomugisha opines that the laws lack sufficient constitutional backing; and the enforcement mechanisms are very weak. There is no attention to public participation and this compromises the wellbeing of the people and the strategies to regulate oil and gas sector in the country (Twinomugisha, 2012). The Constitution vests all minerals and petroleum in, on or under any land or in waters in the Government on behalf of the Republic of Uganda. The Parliament of the Republic of Uganda is mandated to make laws, regulating the exploration and exploitation of minerals and petroleum. Such laws include the Petroleum (Exploration, Development and Production) Act, 2013, the Petroleum (Refining, Conversion, Transmission and Midstream Storage) Act, 2013 and regulations thereof.

Analysis of the Concept of punishment

To begin with, proposition must be given that the concept of punishment seeks to panelize or set penalties against the violators of safety laws or regulatory rules set forth to govern the sector. Proponents and authors contend that the concept of punishment has been heavily relied on in the Extractive Industry (EI) particularly the mining sector and oil and gas industry (Gordon et al, 2008). The Report reveals that the concept of punishment has three dimensions and prepositions which include: (A) To punish or panelize those who violate safety laws and industrial policies (B) To prevent violation of regulatory inspections (C) Punitive in nature.

Due to fatalities and disasters in Extractive industries (EI) particularly the oil and gas sector, serious violation of safety laws was reported in the extractive industry. This made it more necessary to incorporate the concept of punishment in the regulatory framework as a move to control and impose serious penalties on those who violate safety laws (Cave, 2011). The increase in Oil and Gas exploration activities has made countries devoted to serious safety regulations in most jurisdictions. The research reveals that all these fatalities have happened due to weak regulatory framework (Cave, 2011).

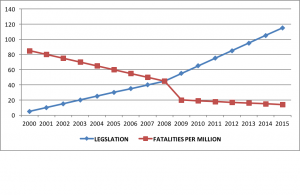

Figure 1 The impact of legislation on fatality rate

Figure 1 The impact of legislation on fatality rate

Source: author

It must be observed from the regression lines in the above figure 1 that between the year 2000 to 2015, the rates of accidents and disasters were too high due to weak safety regulatory framework, and in other jurisdictions there were no regulation at all. The existing regulatory framework was not punitive in nature. As such employees in mining and oil and gas sector consistently breached and violate the rules. From 2011 to 2015, the fatalities reduced due to increase in strengthening policy and legal framework concerning safety laws in an Extractive Industry.

Analysis of the Concept of persuasion

The concept of persuasion has been defined differently by different scholars and authors. According to perloff in his working paper, persuasion means any attempt to change the attitudes, motivations, beliefs and behaviors of one or many individuals. Perloff combines this and other definitions by stating that: “persuasion is a symbolic process in which communicators try to convince other people to change their attitudes or behavior regarding the issue through the transmission of a message” (Perloff, 2003). In an atmosphere of free choice, other scholars contend that regulators have invoked the concept of persuasion as a move to shift from harsh and punitive to a friendly or sympathetic way of enforcing safety laws and standards.

It has been further observed that the concept of persuasion is usually invoked by the regulators and enforcement agencies when there is willingness of the stakeholders in oil and gas sector and mining industry in general to comply and obey safety rules. Conversely, ‘’Perloff’’ writes in his paper that punishment is not the best regulatory regime to guarantee compliance, but rather applying a friendly and sympathetic way may yield good results and compliance.

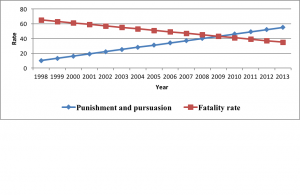

Figure 2 The Synergy between the concept of punishment and persuasion in preventing major fatalities.

Figure 2 The Synergy between the concept of punishment and persuasion in preventing major fatalities.

Source: author.

The regression lines in the above figure 2, illustrates that as jurisdictions incorporated the concepts of punishment and persuasion in the regulatory framework for oil and gas sector, the fatalities and the disasters reduces with increase in enforcement mechanisms.

The Constitution of Republic of Uganda, 1995 (as amended)

The constitution obliges the state to promote sustainable development and public awareness of the need to manage land, air and water resources in a balanced and sustainable manner for the present and future generations. Environmental needs of the future generations must be respected by preventing and minimizing damage and destruction to land, air and water resources resulting from pollution or other causes. Furthermore, the state is obliged to promote and implement energy policies that will ensure that people`s basic needs and those of environmental preservation are met.

The foregoing principles provide basis for Article 39 of the Constitution of Uganda which entrenches the fundamental human right to a clean and healthy environment for every Ugandan. The Constitution empowers Parliament to make laws for the protection and preservation of the environment from abuse, pollution and degradation; management of the environment in a sustainable manner and the promotion of environmental awareness. Most importantly, the Constitution provides for mechanisms of enforcing fundamental rights through courts of law. An individual person, whether he or she is directly affected or whether the affected person knows or do not know, can originate proceedings before court to stop a violation or a threat to any fundamental rights. These constitutional provisions are operationalized by various Acts of parliament and regulations which are considered here below.

The Petroleum (Exploration, Development and production) Act. 2013 (PEDPA)

The PEDPA is the principal Act governing petroleum Activities, the Act commenced on 5th April 2013 and is intended to establish an effective legal framework and institutional structures to ensure that petroleum activities of Uganda are carried out in a sustainable manner that guarantees optimum benefits for all Ugandans, both the present and future generations; through inter alia, establishing institutions to manage the petroleum resources and regulate the petroleum activities, ensuring the public safety and the protection of public health and the environment in petroleum activities. The purpose of the Act was specifically mindful of the need for environmental and public health protection.

Under Section 3, any person performing or exercising functions under the Act in relation to petroleum activities is required to comply with environmental principles and the safeguards prescribed by the NEA and other applicable laws. A person who fails to comply, commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding 2bn shillings or ten years imprisonment or both. The researcher that established the fine of 2bn Ugandan for failure to comply with environmental principles is too easy to mobile in the oil and gas industry. In line with the above, NEMA is mandated to make regulations for management and disposal of waste arising from petroleum activities and such regulations must be laid before parliament. These provisions presuppose that the Act provided sufficient mechanisms to punish and persuade the violators through which such protection would be achieved.

The PEDPA, Section 100 (1) prohibits gas flaring in excess of the quantities needed for normal operational safety without the approval of the Minister on the advice of the Petroleum authority. The section also means that flaring for normal operational safety is permitted; however, the Act does not define ‘normal operational safety’ and this gap could enable unauthorized flaring routine flaring. The definition would be necessary because it would help to highlight the need for flaring in excess of the normal operational safety measure.

Findings from the technical department of the MEMD indicated that it is not necessary to define normal operational safety and the license should not be given fixed positions on technical matters. The same was said of the emergencies that would necessitate flaring without consent of the authority. This argument makes it difficult to distinguish flaring for normal operational safety and for emergency reasons. The examples of emergencies given by the ministry include, pressure build ups in the production system and in case of planned shutdown to prepare for system maintenance.

Subsection (6) imposes a sanction for contravention of subsection (5) and upon conviction a fine of five hundred thousand currency points is applicable. The foregoing discussion indicates that it is difficult to find any licensee liable under this section since there is no unit of measure of gas to be flared as regards the submission of a report. A licensee should always find it easy to comply since it seems impossible to challenge such a report. It is also apparent that the penalty only applies to licensees who flare under emergency circumstances and either fail to ensure that the flaring is kept to its lowest possible level or do not submit the technical report to the authority.

The section allows flaring for normal operational safety, flaring in excess of quantities needed for normal operational safety but with permission from the Minister on the advice of the authority and flaring in case of emergency. What is prohibited is flaring in excess of quantities needed for normal operational safety. This law is inadequate and offers triple opportunity to the licenses to conduct flaring because if flaring is allowed for normal operational safety, anything abnormal would naturally be an emergency in respect of which the license can flare without consent and file the necessary reports.

The other pertinent issue is that subsection (5) requires a licensee to ensure that gas flaring is kept at the lowest possible level and technical report detailing the nature and circumstances that caused the emergency situation. The researcher has established that it is possible to define such circumstances that can cause or amount to emergency for purposes of gas flaring. The requirement to submit a report cannot reverse the damage that may be caused by excessive flaring. Furthermore, the requirement to ensure flaring is kept to the lowest level possible is ambiguous and/or subjective and cannot protect Ugandans and the environment as whole.

The Petroleum (Refining, Conversion, Transmission and Midstream Storage) Act, 2013 (PRCTMSA)

This Act came into force on 26th July 2013 regulating midstream petroleum. It requires that such operations are carried out in a sustainable manner especially ensuring public safety, protection of public health and the environment. With regard to compliance with environmental principles and procedures, the Act repeats section 3 of the EDPA as presented herein above. The same applies to the provision of section 100 of the PEDPA discussed above which reproduced by section 38 of the PRCTMSA. The arguments presented herein on those provisions apply to this Act in same manner with regard to the corresponding noted sections (like the PEDPA, the PRCTMSA) sets sanctions for non-compliance with the provisions set under the Act. The discussion alluded above brings out the true picture of the concept of punishment and persuasion in Uganda’s regulatory regime for oil and gas sector.

The Petroleum (Refining, Conversion, Transmission and Midstream storage) regulations 2018 SI No.36

These regulations assert that the licensee shall not vent or flare except in accordance with the Act. The regulations made under the National Environment Act, approved by the authority and best petroleum industry practices as part of normal operational safety in the refinery, conversion plant or other petroleum process plant ensure that vapors and gases are safely disposed. With regard to flaring, the regulations made by NEMA would include the air quality standards which have remained in draft for over 20 years. The determination of extent of pollution of air will not be possible in absence of such standards.

The regulation also requires the licensee to estimate flared volumes for new facilities during the initial commissioning period so that fixed volume flaring and venting targets can be developed. The volumes of gas flared shall be recorded and reported and continuous improvement of flaring through implementation of best petroleum industry practices and new technologies shall be demonstrated. These appear to be good provisions, but the licensee is given wide freedom of estimating the volume of gas flared for purposes of fixing flaring and venting targets. The authority or the lead agency in the management of the environment (NEMA) ought to participate in the estimation of such volumes in accordance with section 24 (d) of the NEA. This regulation as it is, offers an opportunity to the licensee to set preferred standards of flaring which may put the environment at a greater risk. The provision does not clearly oblige the responsible institutions to determine the amount of the flared gas. Only monitoring duties would lead to continued reliance on the standards/records given by the licensees. The same applies to the recording of the volumes of gas flared and the requirement for continued improvement of flaring technologies in accordance with the best practices in the petroleum industry. Such best practices or technology ought to be dictated by the regulatory bodies to ensure compliance and effectiveness. The above provisions in their current form are quite passively formulated and may be easily avoided by the profit- oriented licensees.

The Petroleum (Refining, Conversion, Transmission and Mid-stream storage) (Health, safety and Environment) Regulations, 2016 (Uganda)

The HSE regulations (R.7 (1) (f) provide for at least 60 meters from the other process units or storage tanks and the flare to conform to standards approved by the authority. A minimum of 60 meters is too short. This could endanger human life. It has been established that flares at 100 meters in Niger Delta have destroyed the environment especially humans. The MEMD noted that 60 meters could be too short or too long depending on the circumstances of each case. The MEMD officers argued that it is not necessary to prescribe such a fixed position since it can condition operations unnecessarily.

The finding from the local community indicate that flaring pollution spread to over 500 meters in the case of conventional flaring. It is, therefore, necessary that provisions had to be made for a distance so that the poorest technology to guarantee safety. These regulations have also been considered. They have no specific provision prohibiting or allowing flaring. What may be relevant is the regulation 22 (1)(e) (ii) which requires the field development plan to provide solutions and technology selected to prevent hazardous emissions to air and discharges to the environment. The regulation implies that there is an opportunity to choose which technology to apply.

Lessons Uganda can learn from other jurisdictions

Like any other jurisdictions, Uganda must consider the notion of National capacity building as essential in order to enable the country to regulate oil and gas sector and Extractive Industry (EI) in general. The government should put more concern on programs designed to enhance economic development and transformation as a tool to archive development, sustainability, endurance and financial prosperity. Economic Development and transformation must focus on development of infrastructure necessary in archiving the desired goals in line with 2020 Uganda’s vision and strategies.

The government through the National Oil Company (NOC) as the participating entity on behalf of the country must opt for strategies designed to use finite resource sparingly. Oil and gas are non-renewable finite resources and the benefits accruing from them is subject to depletion and exhaustion from the field. Therefore, this makes it incumbent to the National Oil Company (NOC) to design mechanisms that are intended to safe guard and manage oil and gas resource in a manner that will create lasting benefit to the society.

Archiving such benefit can be through using such resources to develop competencies through education, infrastructure development together with financial and social capital that can extend even beyond production and decommissioning of the field. Both the National Oil Company (NOC) and International Oil Company (IOC) must take into account the basic principle of intergeneration equity; that is to say, by utilizing the resource not only for the current but also for the future benefit. The activities of the current generation should not put a burden on future generations especially with regard to depletion of non-renewable resources. This is in line with The Petroleum (Exploration, Development and production) Act.2013 (PEDPA) which mandates the state to exploit, develop and produce oil and gas resource in the manner that promotes and guarantees intergenerational equity and sustainable resource management as opposed to accelerated revenue generation.

Uganda as a newly emerging oil and gas producing country in East Africa must put more concern on competiveness and productivity in oil and gas sector. It is through competiveness that licenses, operators and suppliers, that a cost effective choices can be achieved. Competitiveness enables the participating entities in the oil and gas sector specifically the National Oil Company (NOC), the operator, contractor, Local oil companies (LOC) and International oil company (IOC) to maneuver and venture all options designed to archive a competitive advantage. Furthermore, competiveness in the newly created oil and gas sector enables selection of capable operators, efficient, and reliable suppliers to make procurement tenders in the sector.

Challenges of regulating oil and gas sector in Uganda

The Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) is poorly financed, coupled with inefficiencies and weak economies by the governments. Consequently, in other jurisdictions, most of the revenues collected by the National Oil Companies (NOC) are remitted to the consolidated fund and nothing is retained by the National Oil Company (NOC) which is then expected to wait for financing and funding from the state that was never sufficient to enable the National Oil Company (NOC) undertake the ventures that it proposed or sought to undertake. The Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) being newly incorporated entity may find such challenges which other jurisdictions have faced.

Secondly, there is a challenge of weak enforcement mechanism in the country. Enforcement of any laws is not the responsibility of a single institution alone in a country like Uganda which may be considered over-regulated but with the limited action/enforcement. For example, enforcing wetland conservation may require the input of the police force of the department of lands and the courts. If any of these institutions fails on its part, the result is failed wetland preservation. A good example is the issuance of land titles in wetland areas by the central and local governments (UNEP, 2017). This has contributed to environmental degradation since the processes challenging such titles is lengthy.

Thirdly, as already noted, Uganda depends heavily on environment and natural resources. Over 90% of the population directly depends on the products and services from agriculture, fisheries, forests and wetlands among others (UNEP, 2017). The country is faced with several environment-related worrying trends which put economic, environmental and social development at risk. As noted in 1995, the worrying trends constitute oil degradation, deforestation, drainage of wetlands and loss of biodiversity, pollution and unhealthy conditions. This continues happening over 20 years after, and the same trends are still evident.

In 1995, a National Action Plan was set up including a legislative and institutional framework and requirements on Environmental Impact Assessments for all development projects and activities expected to have environmental impact. Responsibility for environmental management was formally devolved to district and lower governments but without equipping them to effectively operate. In view of the presence of highly praised environmental laws in Uganda, the problem is weak implementation capacity by the responsible institutions especially NEMA.

Recommendations

The government of Uganda should exploit oil and gas resource efficiently in order to maximize its returns. This can be achieved by mitigating risks and losses, arising from the same and reducing the Costs of operation, by increasing maximum levels of production on other hand. This will first create mechanism that may promote effective revenue management and engineer economic growth and development. Secondly, the revenues accruing from oil and gas resource must be utilized effectively, equitably and sparingly in order to archive the desired goals for the country.

The relationship between the governments, International Oil companies (IOC) and other stakeholders in oil and gas industry should be maintained in the spirit of mutual respect, Co-operation and trust. Building mutual trust and lasting relationship between the International Oil Company (IOC) and National Oil Company (NOC) can be gained through mutual cooperation and constructive dialogues on the other hand. Co-operation can be extended to communities in oil and gas producing regions and pipeline corridors. It must also be noted that Royalties and other rents arising from extraction of oil and gas resource must be shared in accordance with the constitution and Petroleum Act. Thirdly; efforts must be made to avoid development of conflicts between the government, International oil companies (IOC) and other stakeholders in order to maintain peace and security in the sector.

Furthermore, the government must put concern on financing the National Oil Company (UNOC). Raising funds to finance the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) may be difficult and complex especially in early stages because the available revenues will be utilized to cover costs incurred by International Oil Companies (IOC) and other contractors that invested in exploration, development and production of oil and gas resource. However, the need to finance Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) is more urgent in order to strengthen the entity’s capacity in performing its obligations and implementing its decision on behalf of the country. The Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) as a body newly incorporated should start with minimal resource available and grows slowly by learning from other jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Due to fatalities and disasters in an extractive industries (EI) particularly the oil and gas sector, serious violation of safety laws has been reported and documented in the extractive industry. To address such a challenges, Uganda as a newly emerging oil and gas producing nation has incorporated the concept of punishment and persuasion in the regulatory framework for oil and gas sector as a move to control and impose serious penalties on those who violate safety laws. It has been further observed that the concept of persuasion shall always be invoked by regulators and enforcement agencies when there is willingness of the stakeholders in oil and gas sector and mining industry in general to comply and obey safety rules. Perloff writes in his paper that “punishment is not the best regulatory regime to guarantee compliance but rather applying a friendly and sympathetic way may yield good results and compliance.”

The author of this article hold MA, Int’l Law and Human Rights and he is currently pursuing a second Master Degree of Laws (LLM Oil and Gas Laws). Please don’t ask why not publishing an articles about the South Sudan Oil and Gas safety rule and regulations instead. Writing about the other countries will also give you an insight of what need to be done in the homeland country. Feel free to reach him at [email protected]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

TEXT BOOKS

Baldwin, R., Cave, M., & Lodge, M, Understanding Regulation: Theory, Strategy, and Practice (Oxford University Press,)

Gordon, Patterson, Oil and gas Law Current practice and emerging Trends 2nd Edition (2011)

JOURNALS

The Right to Clean and Healthy Environment in Uganda, Available on <Http://Www.Lead-Journal.Org/Content/07244.Pdf> Accessed on 29/1/18.

Amoako-Tuffour, Aubynn, Attah-Quayson, Local Content and Value Addition in Ghana’s Mineral, Oil and Gas Sectors: Is Ghana Getting It Right? (, Kampala)

century, 2nd ed. Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah.

Kathman, J., Shannon, M, Oil Extraction and the Potential for Domestic Instability in Uganda (African Studies Quarterly, 12(3), 23,)

Lassourd, T., & Bauer, A, Fiscal Rule Options for Petroleum Revenue Management in Uganda. (Revenue Watch Institute)

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development, ‘’the oil and gas sector in Uganda: Frequently asked questions. (December, 2014)

Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st